During my first chancellorship, I was confronted with a significant problem. I was the leader of a campus knee deep in a federal desegregation court case at a time when our faculty and staff ranks showed a conspicuous deficiency of minorities.

Despite my best efforts in my first year as chancellor to push deans to search diligently for African American faculty, we came up empty. The deans consistently told me that they simply could not find qualified African Americans.

The second time around, however, I thought of a strategy to test their assertions. Since the campus was in a dramatic student enrollment growth mode, we had the luxury of funding to support lots of new faculty positions. With that circumstance in mind, I made an offer the deans could not to refuse. Stated simply, I advised the deans that in allocating new positions to the various departments, I was creating five at-large positions that would go to any department that identified qualified African American faculty.

Suddenly, the deans who had persistently told me they could not find qualified African Americans found success. The five at-large positions were gobbled up quickly, and the university topped all other state universities with the highest percentage gain in minority faculty for that year.

While the numerical improvement was important, the real test of the success of the initiative was the academic strength of the five African Americans who were employed. Did the deans compromise quality simply to gain a position and please the chancellor?

The answer was a resounding no. Four of the five proved to be outstanding faculty who built long-term, successful careers in academia. And it all started as a result of an unconventional initiative of a chancellor who genuinely cared.

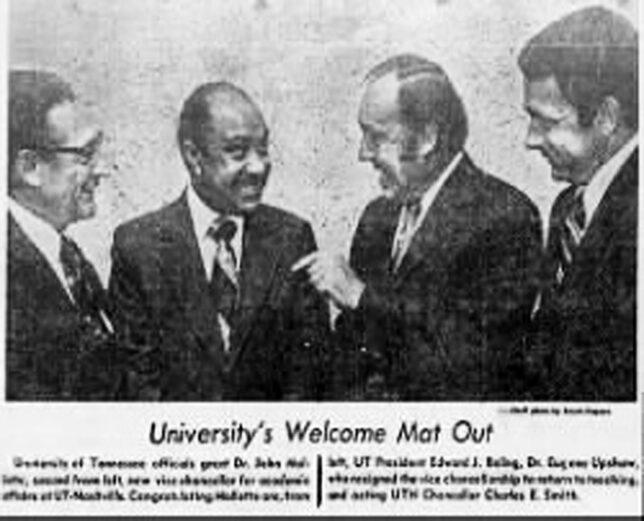

As a footnote to this initiative, I was fortunate later that year to recruit an outstanding African American professor and researcher to the position of vice chancellor for academic affairs. In short order, we had corrected a glaring deficiency within our campus.

Later in my career, perhaps my greatest achievement as chancellor of the Tennessee Board of Regents was the recruitment of African Americans to fill both the chief academic officer and chief fiscal officer positions on the Board staff. In my remarks at my retirement dinner, I noted with pride that the seventh largest university system in the nation was the only system to have the two highest ranked system offices filled by African Americans. Both of those individuals became university presidents. I would like to believe that my actions had something to do with opening up the opportunities they secured.

-adapted from Journal of a Fast Track Life © 2018 Charles E. Smith. All rights reserved.

Top photo courtesty of Lia Castro at Pexels.com