As chronicled in my previous post, my selection as Nashville Banner editor was more than a bit bizarre. However, the story of how John Jay Hooker became publisher of the newspaper takes incredulousness to an even higher level. It is a story of what goes around comes around, with a bitter twist.

The Nashville Banner was Hooker’s number one tormenter in the campaign for governor in 1970. Every day for seven months, the Banner served its readers with a heavy dose of negative stories about candidate Hooker. As his press secretary, I was the one who had to deal daily with the Banner’s poison pen reporters. Arguably, the Banner was primarily responsible for Hooker’s narrow loss to Winfield Dunn in the general election.

So, it was with great irony that Hooker and I walked into the Banner newsroom in August of 1979 as publisher and editor, respectively. A strong dose of karma loomed large on that fateful day. As the old saying goes, you simply can’t make this stuff up!

The triumphant march to the takeover of what had been the home of an adversary out of the past began with negotiations in the latter months of 1978 between the Gannett Corporation and Amon Carter Evans, publisher of the rival Nashville Tennessean.

Gannett owned the Nashville Banner, but chairman Allen Neuharth coveted the larger and more profitable Tennessean. Evans signaled his possible interest in selling. Secret talks began. A big hurdle to overcome was an antitrust provision that required Gannett to sell the Banner in order to buy the Tennessean.

The antitrust issue gave Evans considerable leverage in negotiations with Neuharth. The strong-willed Evans took full advantage of the “chips” he held. He set the price at $50 million for the Tennessean. He insisted that longtime Tennessean editor John Seigenthaler be given a lucrative ten year contract with language assuring total editorial control (something unprecedented for Gannett). And he demanded that Hooker be given the sole ticket to buy the Banner.

Neuharth agreed to all three provisions, the latter of which set the stage for Hooker’s takeover of his old nemesis. However, significant hurdles confronted Hooker. He had the ticket to buy, but he lacked the resources to pay for the purchase.

Thus, the hunt began for well-heeled potential investors. In short order, he brought childhood friend Brownlee Currey into the fold, and Currey, among others, pointed Hooker toward a third potential investor, the unknown but wealthy Irby Simpkins, a brash, ambitious, and temperamental fellow.

In short order, particularly by Hooker’s standards, the partnership deal was struck. Hooker played his ticket to buy, and Currey and Simpkins agreed to put up the $25 million for the Banner purchase. So, Evans got what he wanted, Hooker became publisher of the Banner with a one-third ownership, and Currey and Simpkins were suddenly thrust into an unfamiliar public spotlight with their collective two-thirds ownership.

The honeymoon for the partnership effectively ended in the first week of control at the Banner. A 2:00 a.m. phone call to me from our police reporter alerted me that a suspect had been arrested and charged in the long unsolved murder of young Marcia Trimble – Nashville’s most notorious crime case.

Adding to the drama was a scheduled early morning flight to Dallas for the three owners and me to meet with the publisher of the Dallas afternoon newspaper. Simpkins had set it up, and it was a command performance designed to give all of us a full day of substantive discussion with the well-known publisher who had keen insight into the operation of an afternoon newspaper.

I called Hooker immediately, and he in turn patched Simpkins and Currey into the discussion. All three owners quickly agreed that I had to stay behind and oversee the coverage of the arrest. Hooker also wanted to stay, but Simpkins was insistent that Hooker make the trip. As usual, Currey had little to say.

The debate between Hooker and Simpkins erupted into some heated exchanges with me caught in the middle. I honestly told the owners that I was comfortable handling the on-site management of the story, a comment Hooker clearly did not like. The conversation ended without resolution on whether Hooker would go or stay, even though the private plane flight was scheduled to leave at 5:30 a.m.

Within seconds after the conference call ended, my home phone rang. It was an angry Hooker calling to blast me for not siding with him in the debate with Simpkins. I quickly told Hooker that in our long relationship, particularly the 1970 gubernatorial campaign, I had always told him exactly what I thought on any matter.

He acknowledged that and expressed appreciation for my long- standing candor with him. Then he startled me a bit by stating, “Pal, this is different. It was just you and me in the past. Now we have to deal with a strong-willed guy who is tough as nails. I need you with me at all times with him.”

Our painful phone call ended inconclusively. I did not know whether he would stay with me or go to Dallas with his partners. I arrived at the Banner at 5:30 a.m. and learned about an hour later that Hooker had left for Dallas. I never knew what other conversations occurred in the wee hours of that fateful morning, but obviously, Irby’s will had prevailed. Ominous signs were emerging early in new ownership of the Banner.

As August faded into September of 1979, relative calm prevailed. We were receiving increasing praise for publishing a quality product. Simpkins was preoccupied with the start-up business decisions that had to be made. He essentially stayed out of the newsroom.

However, by mid-September, Hooker was preaching to me and all who would listen that the Banner was committed to shifting from a Republican leaning newspaper to one that was independent in editorial policy, Simpkins began to drop by my office to chat about his increasingly strong belief that the Banner should be Republican.

So, by the end of September, I was the editor of a newspaper whose publisher said we were independent and whose president was proclaiming that we were Republican. While I was able to steer clear of the independent/Republican conflict by focusing most of the editorial positions on non-partisan issues, I knew I was holding a ticking time bomb that was certain to explode at some point.

By mid-October, the power struggle between Hooker and Simpkins had intensified, while Currey remained essentially on the sidelines. I was increasingly being called into meetings with Hooker and Simpkins, where I was confronted with having to take sides on a wide variety of matters. Fortunately, Hooker permitted me to speak my mind, and by so doing, I was able to walk a delicate line that kept me in good standing with both men. Nonetheless, it was becoming apparent that Hooker was gradually losing the power struggle.

Throughout the September to November period, I agonized over the state of the Banner and my position as editor. I loved what I was doing in the newsroom and had considerable freedom to select the content and editorial tone of the newspaper. However, the endless participation in the behind-the-scenes power struggle between Hooker and Simpkins was taking its toll on me. Also, the pain of watching my hero Hooker being slowly diminished by the overbearing Simpkins was excruciating.

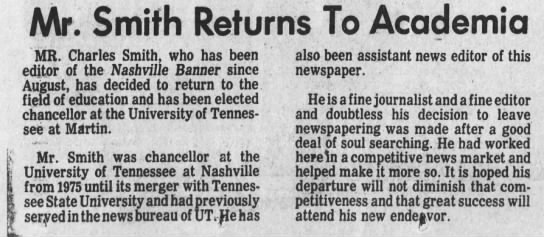

Then in early December, circumstances suddenly changed. The chairman of the chancellor search committee at the University of Tennessee at Martin called me with word that the five finalists for the job I had turned down in July 1979 had been found to be unacceptable. I was asked directly if I had any interest in reconsidering my candidacy. My heart said no, but my head said yes.

Within a few days, I agreed to visit the campus once again to meet with the search committee. Simpkins moved quickly to contact then Governor Lamar Alexander, who called me at the airport while my daughter Tandy and I waited for the UT plane to pick us up. His message was simple: “Charles, speaking as chairman of the UT Board, I want you to know that you have my full support and nothing would make me happier than for you to take the chancellorship at Martin.” It was a nice gesture, but I knew immediately that this was essentially Simpkins pulling some strings to secure my move to Martin and leave Hooker isolated at the Banner.

Upon my return to Nashville from the meeting with the UTM search committee, I contacted Hooker and told him that I would be accepting the chancellorship. He was shaken by my pending decision. He did what he always did during our years together. We went for a ride – one that literally extended over a four-day period.

Starting on a Thursday morning, we took the usual routes: Nashville to Lebanon and back, Nashville to Columbia and back, Nashville to Dickson and back, Nashville to Clarksville and back. Then we would repeat the routes, over and over again until late Sunday. It was a four-day running conversation that was vintage Hooker, using his great oratorical skills as an attorney and keen wisdom as a caring human being to make his case that I stay with the Banner. He spoke with strong emotion that tugged at my heartstrings.

Two constant themes emerged from his message. On one hand, he voiced deep concern that he had let me down by not being stronger with Simpkins. On the other hand, he expressed over and over again his great fear that without me there to support him, Simpkins would be overwhelming. I assured him that he in no way had let me down and that with or without me, he was going to lose the battle with Simpkins. My central message, as I remember well, was, “John Jay, Irby has the money, and when the time is right, he will persuade Brownlee to join him in voting you out of the partnership.”

As the fourth day of riding and talking was ending, Hooker suddenly stopped the car, turned to me with tears flowing down his cheeks, and sadly stated that he recognized that he could not talk me out of leaving.

A few months later, my prediction came true. Simpkins won the power struggle. Hooker was bought out and removed as publisher. What began as a beautiful, too-good-to-be-true dream had ended sadly for Hooker and all who loved him.

Simpkins assumed the publisher’s role and used the Banner to reward his friends and punish his enemies, lists that changed with the weather. Hooker and Simpkins remained bitter enemies until Hooker’s death in 2016.

Simpkins eventually bailed out of the Banner and embittered practically everyone who worked there. He quickly lost the power he coveted once he sold the Banner. He often shared with his few remaining friends his puzzlement that no one seemed to want to return his calls anymore. He would often invoke the name of former Tennessean editor and publisher John Seigenthaler and note sadly that he didn’t understand how Seigenthaler continued to be a power broker until the day he died, long after he retired as the Tennessean publisher.

Indeed, Seigenthaler was a power broker, the best I’ve ever seen. However, his power was anchored by his strong intellect, great courage, and demonstrated ability to respect his friends and foes. In short, he had character and principles that earned him respect, exhibited by the thousands who attended his funeral services and related events.

I’m not sure Simpkins ever understood that. What goes around comes around!

-adapted from Journal of a Fast Track Life, Chapter 27, © 2018 Charles E. Smith. All rights reserved.